If you are one of the many admirers of the 1968 American classic Bullitt starring Steve McQueen (my recommendation here), you will almost certainly enjoy the British film Robbery. Released the year before Bullitt, it’s a partly fictionalized account of the astonishing 1963 heist of a British mail train by a gang of bold and crafty thieves.

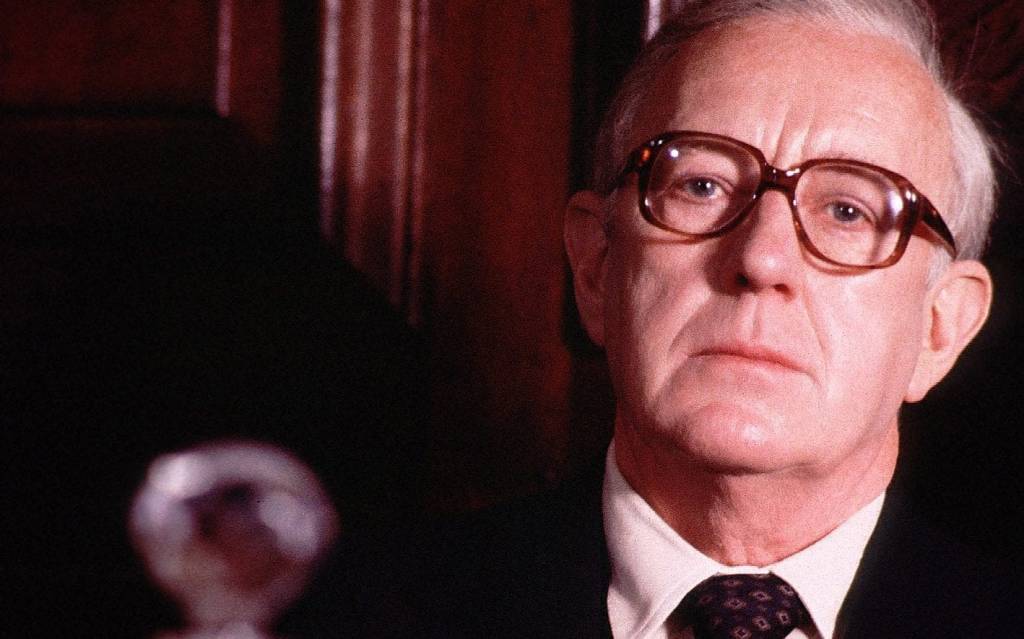

Like many heist films, this one begins with a smaller job that introduces us to the characters and sets up the big score to come. The gang upon which the movie centers is led by criminal mastermind Paul Clifton (Stanley Baker, who also produced). Baker was one of a number of rough-hewn leading men who captivated British audiences in the 1960s. One wonders if we would have ever heard of a similar actor — Sean Connery — had Baker not turned down the offer to play a secret agent named James Bond (Side note: It is nothing less than eerie to see how much an older Baker looks like an older Connery in later projects such as the ITV mystery special Who killed Lamb?). In all his roles, Baker radiates power, even as in this case when his character is intellectual and non-violent. Credit him here also with first-rate production values on a film was no doubt good practice for the studio that would go on to make The Italian Job.

The gang escape their first job after a harrowing, thrilling car chase through London, but they don’t spend the money. They need the swag to fund something much bigger that Clifton is planning. The actors playing Clifton’s crew all turn in good performances, as does James Booth as the Police Inspector who doggedly pursues them. We don’t get detailed back stories on any of the characters, but it doesn’t matter because the actors are talented enough to bring them to life and make them distinct.

It was the amazing car chase, much of it shot with handheld cameras by the great Douglas Slocombe, that made Steve McQueen chose Peter Yates as the Director for Bullitt. But that isn’t the only parallel between the two films. Unusually for a director gifted at action films, Yates is comfortable with long silences and seems to encourage his actors to underplay their parts. It creates a distinctive mood that is somewhat melancholy, which fits the many of Yates’ characters who are driven to do things that seem very unlikely to satisfy them in the end.

The bulk of the film is devoted to the painstaking preparations of the gang to pull off the crime of the century, and then the heist itself. As in the actual great train robbery, a number of things go wrong, giving the police a chance to track down the gang and its crafty leader. The resolution of the film is perhaps a bit sudden, and there are a few draggy spots, but overall it’s a solid caper film that will please fans of the genre.