I often recommend multiple movie adaptations of the same story (e.g., The Lodger, Dracula, The Hands of Orlac) for the enjoyment and education that comes from comparing how the same material has been filmed by different artists in different eras. H.G. Well’s classic novel War of the Worlds presents an opportunity to make a different type of comparison, namely between strong adaptations in two different media: radio and film.

I’ll begin by recommending the 1938 radio adaptation (click here to listen). To the extent people have heard of it at all, they know it as the show that allegedly drove America into a national panic about invading Martians (in truth, very few people actually listened to the broadcast). What it ought to be remembered for is its high level of artistic achievement.

The radio play was performed by the Mercury Theater troupe founded by two wildly talented people: Orson Welles and John Houseman. Howard Koch, who later became justly famous as the co-scripter of Casablanca, gets the credit for brilliantly adapting H.G. Wells’ novel to radio in a fashion that took advantage of everything the medium and the Mercury Theater company could do. The novel’s rather lengthy set-up chapters and some of its clunky plot development (i.e., having the narrator run into someone who provides crucial information) were a function of the book being told through the eyes of a single narrator. In contrast, staged as a fake news broadcast with scattered, breathless, reports coming in as the Martians wreak havoc, the radio play grips the audience by the lapels immediately, giving a range of details from different geographic locations in an utterly realistic fashion.

Radio also of course opens up opportunities to accentuate the power of sound — the screams and footfalls of panicked crowds, the horrible, metallic, unscrewing of the Martian cylinders, and the terrifying zzzaaapppp of those heat rays! It’s high craftmanship that still leaves us the fun of imagining how it all looked

Last, but not least, what an explosion of talent this troupe of actors represented! Not just the big names, but also people like Ray Collins, Dan Seymour, Kenny Delmar, and Frank Readick. They are all masterful at creating characters with voice alone, each of whom seems like a real human being responding to out of this world events. Some New York theater fans were disappointed when talented, stage-trained actors they admired began transferring to new, middle brow, media like radio and film, but the upside was that the whole country and indeed the whole world got to enjoy the dramatic gifts and skills of companies like the Mercury Theater.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-2127116-1438792733-9539.jpeg.jpg)

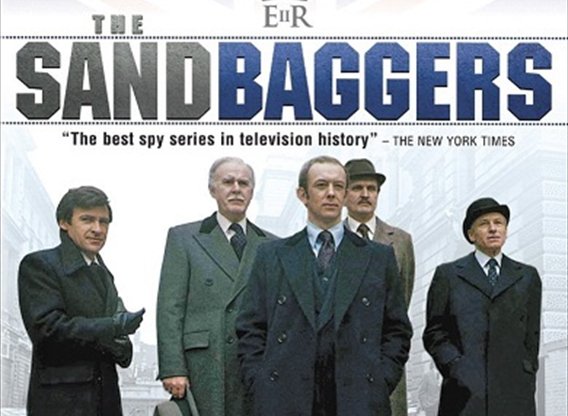

I loved listening to radio play as a kid (the image here is of the record album of it my parents owned) and it’s just as suspenseful and exciting for me today. The radio adaptation of War of the Worlds is in the public domain so you can give it a listen anytime.

The most widely known cinematic version of the same story is probably the Steven Spielberg/Tom Cruise mega-buck 2005 adaptation. But the sci-fi magic that duo summoned in the superb Minority Report was nowhere in evidence in their dreary, weirdly lifeless, take on H.G. Wells. You’d be far better off revisiting the work of another talented pair of frequent collaborators, producer George Pal and Director Byron Haskin, who made a groundbreaking version of War of the Worlds in 1953.

Barré Lyndon, like Orson Welles, took creative license with the original material to create a story telling style that worked well in a new medium. The film opens with two set up narrations, the longer of which, by Sir Cedric Hardwicke, is coupled with an imaginative tour of the planets in our solar system (at least as understood long ago). We then get straight into the action, with the crash landing of a mysterious meteor near an all-American small town (this time, in California). The townspeople are curious, the aliens are aggressive, the military is helpless, but luckily a sturdy Gene Barry as the heroic scientist and a believable Ann Robinson as his love interest and fellow crusader against Martians, are on the job. The quick-moving plot has many parallels with the original work, with the addition of some religious themes that likely played well in the 1950s America.

In addition to the exciting story, what wowed audiences about this movie were the trend-setting, Oscar-winning, special effects. Force fields, laser guns, exploding landmarks, devastated cities, and creepy Martians are among the sights on which to feast your eyes and ears. Of course modern computer-created effects are slicker, but for 1953, this was gobsmacking stuff that showed what movie magic could add to a Victorian English novel.