The 1957 Wolfenden Report kicked off a decade-long debate in Britain over whether consensual sex between men should be illegal. In that era, British police regularly jailed gay men on charges such as “gross indecency” and “homosexual acts”. Men with economic means and status were rarely among the arrested, but they were soft targets for blackmailers. In this environment, it was nothing less than daring to make 1961’s Victim.

The plot of the film concerns a barrister named Melville Farr (Dirk Bogarde), so successful in his profession that he has been asked to take silk at the tender age of 40. His life radiates conventional respectability: Cambridge education, comfortable house in an upper-middle class neighborhood, lovely and devoted wife (Sylvia Sims, very strong in a complicated role). But everything comes unraveled when the police inform him that a young gay construction worker named “Boy” Barrett (Peter McEnery) has hanged himself, and has left behind a series of photos and news clippings which suggest that he and Farr had a strong emotional attachment. The police tell Farr that Barrett was being blackmailed, leading Farr on a righteous hunt for the perpetrators. But the risk to everything Farr possesses is enormous, for the blackmailers have a photo that can reveal his sexuality to the world.

Dirk Bogarde, who was gay in real life, personally lifts Victim from good to great. The handsome star was a screen idol of the teeny-bopper set in the 1950s, but with this movie he turned his back on all that to begin a far more artistically remarkable career in offbeat and challenging movies. Even though Janet Green and John McCormick’s script designs Farr to be as unthreatening to audiences as possible (He is married, resists his homosexual urges and, like Bogarde himself, stays in the closet), taking the role was a risk to Bogarde’s emerging stardom. And the performance itself, with thick layers of British composure hiding surging rage and sexual desire, hits discerning viewers like a thunderbolt.

The script has two other important virtues. The first is its unwinding of the blackmail mystery, which includes a superb bit of misdirection followed by a most intriguing portrayal of the criminals’ motives. Second, the script is sensitive to how different heterosexuals come to a position of tolerance of gay people. A friend of Barrett’s tells him sympathetically “It used to be witches” who were persecuted, and we find out later his sympathy comes more from pity for gays than respect. In contrast, in an understated and moving exchange, Farr’s law clerk tells him simply that he has always respected Farr’s integrity and sees no reason to change his mind upon learning that Farr is gay. Unlike Barrett’s friend, the clerk sees Farr as an equal, indeed even a role model.

Victim is one of many films made after the war by the team of Director Basil Dearden and Producer Michael Relph. The two were recently awarded the distinction of a Criterion Collection boxed set, and there has been an effort by some critics in recent years to say that their talents have been grossly underrated. I recently went on a little binge of watching their films, and I must say that Dearden and Relph strike me as justly underrated filmmakers. I often find myself drumming my fingers because of the leaden pacing of most of their films (e.g., Woman of Straw). I also dislike their occasional lapses into heavy-handed music, speechifying and camerawork and I sometimes suspect that they didn’t have sufficient emotional understanding of the controversial material with which they were often working. Their filmmaking is serviceable, but I suspect a more talented producer-director team could have made every one of their movies better.

It is thus not surprising to me to have read that it was Bogarde who demanded the key scene of the Victim, in which he speaks passionately of his desire for another man (a mainstream movie first) and explains so movingly to his wife the emotional vice that his closeted life places on him. Bogarde personally gives psychic weight to Victim that was lacking in, for example, Sapphire, a less successful Relph-Dearden effort to make a social message film (That one was about race — not bad really — but just not in the same league as Victim).

Given the talent of a remarkable lead actor and a strong script, even a middling producer-director team can make a classic movie, and that is what we have in Victim. It succeeds both as social message and as art, and also may have contributed to the decriminalization of homosexuality in Britain in 1967.

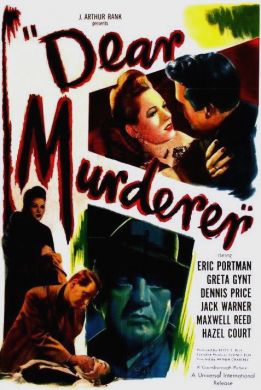

p.s. Kudos as well to another gay actor — Dennis Price — for taking the risk to play another prominent victim of the blackmailers.