Steve McQueen had an incredible run of hits in the 1960s, which put him in position to start his own production company. Solar Production’s original six film deal with Warner Brothers eventually fell apart and only resulted in one film, but what a film: Bullitt.

The first time through, what stays with most people about this film is the legendary car chase. If you watch carefully, you will notice how cleverly and economically the sequence was filmed. The slow-driving green VW bug that keeps appearing is the tip-off: The same incredible driving stunt was filmed from many different angles and then seamlessly edited to look like a series of death-defying maneuvers.

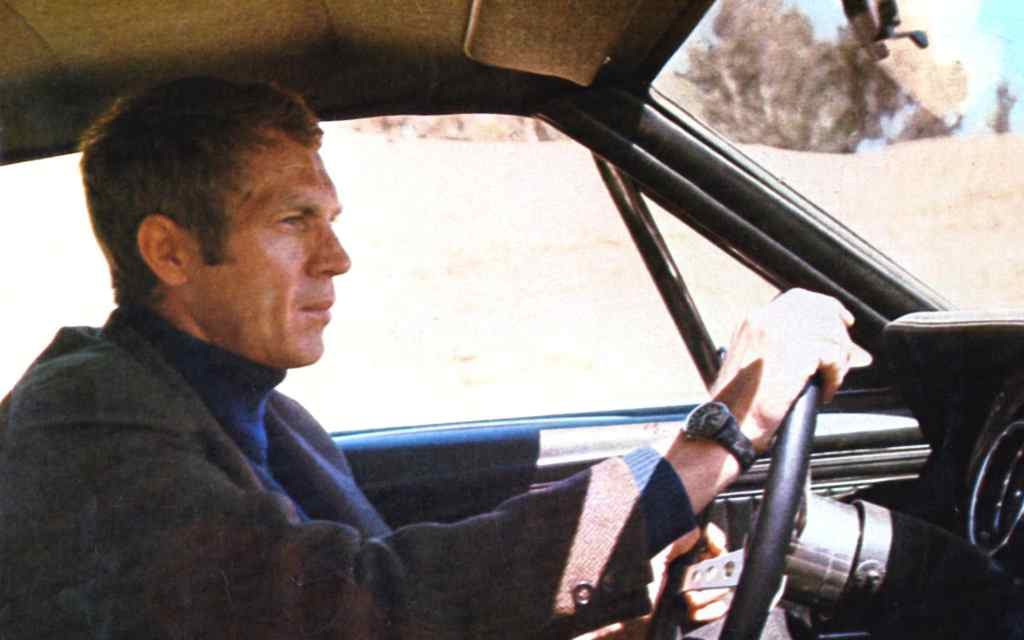

But the thing to watch in the film is Steve McQueen, in one of his very best roles (the completely original Junior Bonner, which Solar Productions made later, is my other favorite). He is a man detached. With loud, free and colorful 1968 San Francisco all around him he is quiet, controlled and dark. Bullitt has closed himself off emotionally to cope with the horrible things he sees as a police officer. As a result he is almost completely alone in the world,

As a Senator hoping to make his political name as a crime buster, Robert Vaughn is also excellent and almost seems to compete with McQueen over who can underplay his part more. Vaughn, along with Simon Oakland as the police captain who supervises Bullitt, embody Hollywood’s traditional portrayal of the law enforcement establishment which McQueen can react against, allowing him to create something new in cinema: a left-wing coded police officer who was hip and counter-cultural. Jacqueline Bisset, in addition to being easy on the eyes, delivers the goods in her dramatic scenes as the one person to whom Bullitt is willing to be somewhat vulnerable. And the ambience of the film is magnificently enhanced by the visuals of the the City by the Bay and the super-cool score of Lalo Schifrin.

Director Peter Yates, then little known outside Britain, got the job of the strength of his breathtaking car chase sequence in the fine 1967 caper film Robbery. But he obviously had skills well beyond that, including the ability to sprinkle high-octane action sequences into crime films that are more often meditative and character driven. A trilogy of my recommendations, namely this film, Robbery, and The Friends of Eddie Coyle, which Yates made over a fruitful 5-year period, illustrate his talent for smoothly weaving high-key moments into fundamentally low-key movies.

Bullitt works as a detective story, as an action film, and as a character study all at once. And it holds up very well under repeated viewings, so even if you’ve seen it before you can treat yourself again to a classic piece of American cinema.