Hollywood studios were in a rut in the late 1950s and early 1960s, struggling to cope with the rise of television, the loss of control of movie theaters after the Paramount case, and a widening cultural chasm between modern audience tastes and studio traditions. In desperation, the studio chiefs opened up filmmaking to a wave of young actors, directors, producers and writers who re-energized American movies, making them arguably the world’s trendsetters from the late 1960s through mid-1970s. One of the pivotal movies from this fertile period in American cinema is 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde.

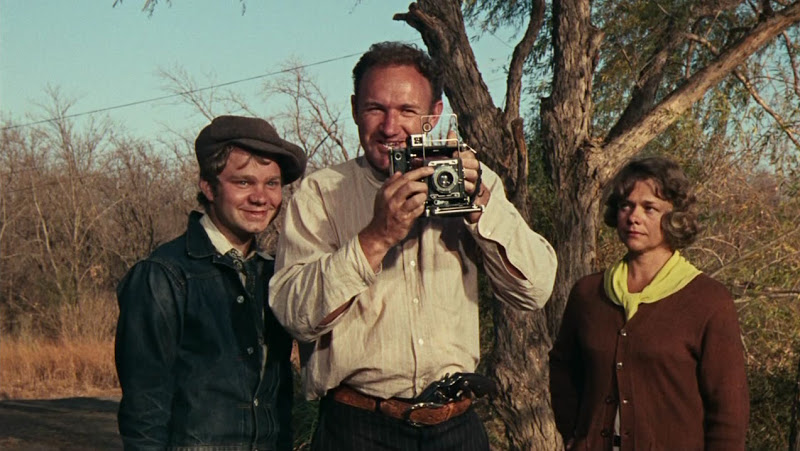

The story opens with a bored, sexually frustrated small town girl (Faye Dunaway) meeting a charming bad boy (Warren Beatty). She questions his courage and masculinity, and he shows off by drawing a gun and committing a robbery. They flee her backwards hometown together, intoxicated by freedom, danger and each other. More daring robberies follow, and with it growing fame for Bonnie and Clyde. Soon they gather other people around them, including a slow witted ne’er do well (Michael Pollard), Clyde’s older brother Buck (Gene Hackman) and Buck’s prim, God-fearing wife Blanche (Estelle Parsons). The law of course comes after them, spurring epic gun fights and a wild cross-country chase sparked with episodes that are surreal (the mesmerizing family reunion scene, which was shot by putting a window pane in front of the camera) and comic (the best of which features Gene Wilder, in his first movie). The story’s conclusion, which I will not spoil, is justifiably one of the most famous scenes in the history of American cinema.

The sexuality and graphic violence on display here was beyond anything Hollywood films had done since the Hays Code came into force in 1934. This is one of the first movies to use squibs and to show bullet wounds spouting blood. The impact of the violence is further amplified through use of the choppy editing style that been popularized by the French New Wave. Also, in a striking reversal of the typical gender roles of films in the 1950s, the woman is the confident sexual aggressor and the man is sexually timid and indeed non-functional (in early drafts of the script, Clyde was in a gay relationship with one of the men in his gang, but in the final version he instead is impotent). The point of view of the story was also novel and in keeping with the rebellious spirit of the times: The heroes are murderers who mow down police officers without compunction.

But it is not just the sexual and violent themes that make Bonnie and Clyde a landmark American film, it is also the movie’s meditation on fame. The criminals’ exhilaration in their notoriety, their self-conscious pursuit of increased publicity and the way they are hero-worshiped by strangers highlight the absurdity of American celebrity culture in supremely effective fashion.

As for the acting, under Arthur Penn’s direction, the entire cast explodes off the screen. Parsons won an Academy Award for her performance but any of the leads and supporting players would also have been worthy choices. Last but certainly not least, Burnett Guffey’s “flat style” camerawork — a complete inversion of his remarkable work in films I have recommended like My Name is Julia Ross, In a Lonely Place, and The Sniper — is one of the lasting achievements in Hollywood cinematography. That Guffey could early in his career thrive in the deep focus, shadowy, stylized world of film noir yet later became a leading exponent of unadorned, naturalistic cinematography shows that he was truly one of the giants of his profession.

The backstory to this film has also become part of its legend. Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker were of course real-life bank robbers in Depression-Era America. The script of this film was brilliantly adapted from their exploits by David Newman and Robert Benton, with uncredited help from Robert Towne. (The latter two of these men, like so many of the people associated with the film, soon became major figures in American cinema). The writers tried unsuccessfully to recruit a French New Wave director to make the movie, but none of them were ultimately interested. Fortunately, Warren Beatty saw the potential of the story and bought production rights, eventually signing Penn as the director. As a sign of how out of touch studio executives were with 1960s audiences, the suits at Warner Brothers were so sure it would bomb that they were comfortable promising Beatty 40% of the gross receipts. They barely released and minimally promoted the picture, and were not surprised when establishment movie critics sneered at it. But it hit audiences like a thunderbolt, becoming a massive box office hit. Remarkably, some chastened film critics went so far as to publicly apologize for their dismissive reviews and to write new reviews praising the movie (except for the New York Times’ insufferable Bosley Crowther, who campaigned against the film so vigorously that his bosses finally realized that it was time to find a more discerning critic). Many years later, this initially unwanted, disregarded and disrespected film became one of the first movies selected for preservation by the National Film Registry.

p.s. If any film prefigures Bonnie and Clyde in American cinema, I think it’s Joseph Lewis’ extraordinary 1950 movie Gun Crazy. If you have time for a double feature, that’s the film to pair with this one. And if you have time for a triple feature, throw in Lewis’ My Name is Julia Ross to appreciate the incredible range of cinematographer Burnett Guffey.