If God could do the tricks that we can do, he’d be a happy man.

The late Peter O’Toole signed on to many over the top, unconventional films (no small number of them when he was intoxicated). This resulted in him headlining some legendary stinkers (e.g., Caligula). But it also landed him plum roles in off-beat masterworks such as The Ruling Class (recommended here) and The Stunt Man.

The film was released to only a handful of theaters in 1980 (In O’Toole’s words, “it wasn’t released, it escaped”) because the studios had no faith in it. Some critics found the film pretentious, manipulative and tiresome, yet it ended up on other critic’s best of the year lists and landed three Oscar nominations. Over time it has attracted a cult following, which it very much deserves, despite its flaws.

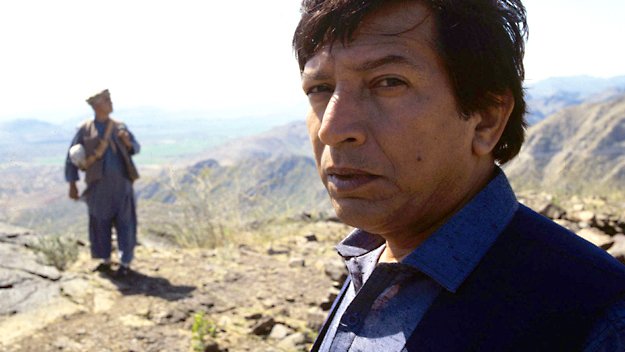

The Stunt Man is a film that messes with the minds of the characters — and with the audience’s as well — by relentlessly mixing movie fantasy with reality. The unreality is embedded in the plot from the first. An alienated Viet Nam veteran named Cameron (Steve Railsback) is wanted for an unknown crime and flees the police, only to find himself in what seems to be World War I. But it’s actually a war movie being directed by Eli Cross (O’Toole). Cameron has a run in with a man he thinks is trying to kill him, but who turns out to be a stunt man shooting a scene. The stunt man dies, and Cameron may or may not be responsible: only the film shot of the event by Cross could reveal the truth. As the police close in, Cross makes Cameron a bizarre offer: to hide within the movie company as a replacement stunt man so that Cross can complete the movie! Cameron agrees, and from then on is manipulated, tricked and exploited while simultaneously trying to romance the lovely starlet Nina Franklin (Barbara Hershey), who seems to have genuine feelings for him…or is that just a manipulation too?

Yes, it’s one hell of a set up. But then again, the script is adapted from a novel in which all the lead characters are insane. The writer/director was Richard Rush, an eccentric, talented but ultimately unsuccessful Hollywood figure whose erratic career path is probably worth a novel of its own. If everyone has one great movie in him, this is Rush’s, and he went for broke, mixing black comedy, action, romance, suspense and satire with largely successful results.

The best thing about the film is Peter O’Toole, who turns in another of his unrestrained, arch performances as Eli Cross. His part is written to be larger than life, and he plays it to the hilt. They say the best roles for British actors are kings and drunks. O’Toole played many of both in his career, and was in real life a King among Drunks. It wasn’t happenstance that he was nominated for an acting Oscar 8 times yet could never quite seal the deal with Academy Award voters (The Stunt Man was one of those disappointments). His distinctive style and obvious talent draws most of us in, but at the same time his flamboyant performances put a significant minority of people off because they feel that he is just playing Peter O’Toole again.

Other strengths of the film are the memorable score by Dominic Frontiere and some vivid supporting performances which help compensate for Railsback being rather one-note as the film’s hero. Also, true to its name, this film is full of jaw-dropping stunts.

The script, with its movie-in-a-movie, riddle-in-a-riddle structure is a matter of taste. I found it a work of near-genius, but I can understand why other viewers consider it exhausting and even alienating. This scene from the film gives a sense of the proceedings, and the compelling nature of O’Toole’s appropriately theatrical portrayal of a mad genius filmmaker. Give this unusual film a chance and make your own judgement.