Artistic concepts and projects can span the world. If Shirley Jackson’s classic American short story The Lottery could be said to have an Albanian parallel, it would be Ismail Kadare’s novel Broken April, which a French and Swiss production group, in alliance with some very talented Brazillians, turned into 2001’s Behind the Sun.

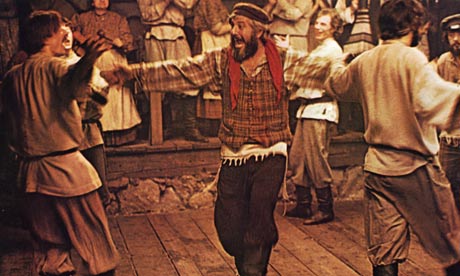

The story is extremely simple, almost an Aesop’s fable. In rural Brazil in 1910, a family of sugar cane cutters has been feuding for generations with a family of ranchers. The conflict began when some land was stolen and one member of one of the families killed a member of the other. In response, the victimized family took precise revenge, killing one but not more than one of the members of the perpetrating family. That family then responded in kind. Over the decades countless members of both clans have died, but no one seems interested in stopping — or even questioning — the tradition of violence other than a young boy in the cane cutting family who goes by the name “Kid”. Meanwhile, an alluring pair of circus performers appear on the scene, with the potential to change the life of the “Kid” and that of his beloved older brother Tonho (played with vulnerability by Rodrigo Santoro), who is next in line to be murdered.

This is a movie of staggering beauty photographed by Walter Carvalho, a superstar of Brazilian film of whom most Americans have never heard (Director Walter Salles is somewhat better-known outside of Brazil, but not as much as he deserves). The arresting visuals are often accompanied by stylized, amped up sound, with a murderous chase through the cane fields being particularly hard to forget.

The acting is uniformly fine, including by the young Ravi Ramos Lacerda as “Kid” (He acquires another name — Pacu — as the film progresses). The actors draw us into a world of brutal simplicity leavened by moments of magic and tender affection. These latter moments are critical because the humanity that the actors infuse into the characters is precisely what makes the unreasoning doom that hovers over all of them so terrifying and maddening.

If you are one those readers who finds the symbols and allegory in much of Latin American literature to be heavy-handed, you may have a similar reaction to aspects of this movie. But even if the Gabriel García Márquez-esque story touches put you off a bit, it should not blunt your appreciation for this powerful, poetic piece of cinema. The exquisite visuals and heartfelt performances are virtually impossible not to appreciate.

Behind the Sun wasn’t promoted effectively when it was released, and as a result did not receive the audience attention it deserved. But those who found it constitute a band of fierce admirers which you would be fortunate to join.