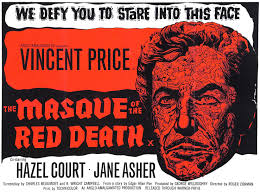

Low budget film genius Roger Corman once said the two films he was proudest of were The Intruder (a searing film about racism and civil rights which I recommended here) and the superb horror movie Masque of the Red Death.

Corman had been enchanted by Edgar Allen Poe stories since reading The Fall of the House of Usher at age 11. After directing a number of schlock black-and-white films made in 10 day shoots, he persuaded James Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkhoff to let him do a Poe adaptation and to make it a “big budget” movie: Not only would it be in color, but he would have 15 whole days to shoot it! With his usual brilliance at spotting affordable talent, Corman cast as the lead Vincent Price, an actor who otherwise might have faded into obscurity along with his youthful good looks. The Fall of the House of Usher proved a big money maker, and an enduring cinematic collaboration was born (Corman, Price and Poe, often joined by other terrific horror actors and writers).

I have recommended the Corman-Price-Poe film Tales of Terror, which while a lot of fun is not as impressive cinematically as Masque of the Red Death. The latter was filmed in the United Kingdom because the government at the time had a film production subsidy policy, giving Corman more to work with financially than usual. The film also benefited from the cinematographer being the gifted Nicholas Roeg, one of the many soon to be famous film artists who was nurtured in the university of Roger Corman. Couple those virtues with Corman’s scrounging ability — he recycled much of the opulent set of Becket here — and you have the best looking of any of the Corman-Price-Poe films.

The plot of this 1964 release comes from the Poe story of the same name, with a subplot drawn from Poe’s Hop-Frog. The story opens in a foggy forest in Medieval Italy, where a mysterious figure cloaked in red foretells of a coming plague (His face is never seen, and I assumed his wonderfully sonorous voice was provided by the late Christopher Lee, but it turns out to be John Westbrook). Meanwhile, the rich, cruel, Satan-worshiping Prince Prospero terrorizes the peasants, and casts a lustful eye in particular on a lovely, impoverished lass named Francesca (played by Paul McCartney’s one-time beau Jane Asher). As the plague spreads through the land, Prospero’s castle fills up with both his greedy courtiers and his unwilling prisoners. Debauchery and nastiness ensue, coupled with ample surrealism and existential dread for good measure.

Corman was utterly in command of his material by this penultimate entry of his Poe cycle, and benefited from a strong script by R. Wright Campbell and the legendary Charles Beaumont (co-creator of the Twilight Zone). The almost hallucinatory ambiance of the film makes it both uniquely unnerving and a foreshadowing of the more experimental film style that would flower as the 1960s went along (including the moments when Corman strains for artiness a bit too much). As for the actors, this may be Vincent Price’s most impressive horror performance: he dominates every one of his scenes. Of the many good supporting performances, particular praise is in order for the little-known Skip Martin. As Hop-Toad, a wronged dwarf who seeks revenge, Martin conveys impressive emotional power. He had the bad luck to work in the pre-Peter Dinklage era where good parts for little people were virtually never written into films, but at least he made the most of his opportunity to shine here.

Masque of the Red Death succeeds as a horror film and also as an art house drama. Congratulations to Corman and his crew, as well of course to the magnificent Edgar Allen Poe.

![Invasion of the Body Snatchers | film by Siegel [1956] | Britannica](https://cdn.britannica.com/67/172367-050-3F9D0E9F/Kevin-McCarthy-Dana-Wynter-Invasion-of-the.jpg)