Of the many film series of the 1930s and 1940s, Sherlock Holmes stood out both for its watchability and its unusual provenance. It was launched at 20th Century Fox in 1939 as a high-end period production. But after two very strong films, The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (my recommendation here), Fox unaccountably dropped the series. Enter Universal Studios, who retained the lead actors and moved the series to modern times (Partly for WWII morale building and partly as a cost-cutting measure). Universal made a dozen modestly budgeted Holmes films in rapid succession over the next four years. Financial constraints and breakneck speed of production were no barrier to quality in this case. None of the films are bad and several are outstanding, including 1944’s The Scarlet Claw.

The plot: Holmes and Watson are in Canada, participating in a conference about the occult. Holmes’ open skepticism about the supernatural irritates the organizer, Lord Penrose (Paul Cavanagh). Penrose gets a message that his wife has been murdered, and the meeting is abruptly adjourned. Holmes presently receives a telegram sent by Penrose’s wife just before her death, saying that she feels she is in grave danger and wants Holmes to help her. Despite Lord Penrose’s hostility to him, Holmes sets off for the fog shrouded town of La Mort Rouge, where the locals believe a monster is ripping the throats out of livestock and also people. The monster is targeting particular individuals for some mysterious reason…can Holmes discover the motive behind the grisly crimes and save the next intended victim?

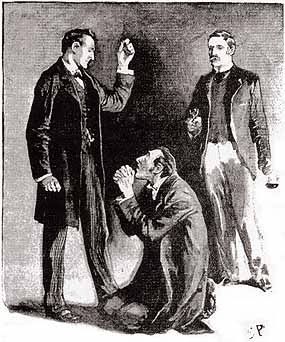

The heart of the Universal series are the triumvirate of Producer-Director (and in the case of The Scarlet Claw, co-screenwriter) Roy William Neill and stars Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce. With his mien, delivery and intelligence, Rathbone was born to play the king of detectives and he defined the role for a generation through appearances on radio, television, film and stage. Neill and Bruce decided to make Watson much more comic than he was Doyle’s stories, which irritated some Baker Street Irregulars. If you can let that go and just take the performance for what it is, you will appreciate that Bruce is indeed agreeably funny in the role and also contributes some moments of emotional warmth which balance out his calculating machine of a friend.

The Scarlet Claw is a high point of the series in part because it feels like an old-fashioned Victorian Holmes story even though it is set in the present day. Unlike in prior entries, Holmes is not battling Nazis but a killer who is (as in many of the films) a pastiche from the original stories. The moody, dark surroundings in rural Canada could easily pass for the Baskerville estate in Dartmoor. Also on display are some first rate make-up and special effects work, which is essential to the story for reasons I will not reveal. The film is also the career highlight of little-known British character actor Gerald Hamer, who makes the most of the opportunity to demonstrate his versatility as a performer. Cavanagh, a handsome, solid B-movie actor with aristocratic bearing who appeared in several films in the series (Including the House of Fear, which not incidentally recycles sets from Sherlock Holmes Faces Death) and also in another of my recommendations, (The Kennel Murder Case) is fully at ease in the role of Lord Penrose. The script is strong and Neill by this point in the series had mastered every aspect of how to create fine Holmesian cinema. The result is a skillfully made, suspenseful mystery.

More generally, as a body of work, the Universal Sherlock Holmes films depart too significantly from the original stories for some people’s tastes, but in performances and atmosphere they stand shoulder to shoulder with the tremendous Soviet Livanov-Solomin and British Granada television versions as high-quality, sustained efforts to adapt Conan Doyle’s beloved stories to the screen. Also, the prints of these films have been beautifully restored by the angels at the UCLA film preservation archive. Scarlet Claw is my favorite, but you could pick up almost any of the Universal series and have a fine evening watching the world’s greatest detective work his magic.