The period between the war and the sexual revolution was disorienting for many American men and women, as prior standards of sexual behavior lost their hold without a clear sense emerging of what would become the norms of the future. In this terrain, Jules Feiffer scripted an unproduced play about the sexual development and relationships of two male college friends. Director Mike Nichols saw potential in the project to become a movie, and the result was 1971’s Carnal Knowledge.

Though sometimes billed as a comedy, the film is actually a melancholy drama and exploration of an era. The central characters are Jonathan (Jack Nicholson), who sees women as sexual objects and pursues them aggressively, and his diffident best friend Sandy (Art Garfunkel) who puts women on a pedestal from which they cannot escape. The film charts their sexual course in three acts running through the 1950s to the early 1970s (kudos to the makeup artists for aging the cast convincingly). The plot centers on the relationships they both have with a college student (Candice Bergen) and Jonathan’s subsequent romance with a gorgeous model who longs for a conventional marriage and home life (Ann-Margret).

The story’s origin as a play is well-exploited by Nichols, who keeps the cast small and the emotional tension high. There is an unreality in much of the staging and shots (such as the above) with only a few characters appearing in camera view at a time. The film also plays with the fourth wall, with characters seemingly giving speeches to the audience until it is subsequently revealed that they are talking to each other. Such theatricality can backfire in film, but in Nichol’s hands, it’s golden.

Nichols’ talent as a director is also evident in his getting first-rate performances from Art Garfunkel, Ann-Margret and Candice Bergen, none of whom is a first-rate actor. If I were king, I would love to see this precise story told again from the women characters’ point of view. The two female leads leave the audience wanting more and guessing so much about their motives as they — like many women of the era –try to navigate a sexually changing world where they are ostensibly freer yet somehow end up even more trapped by convention and male chauvinism than ever before.

Nichols has a penchant for making movies in which none of the main characters are likable. In Closer and the wildly overrated Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? this made for excruciating cinema. But in Carnal Knowledge, Jonathan and Sandy — and even moreso the times that make them — are consistently intriguing despite never being entirely pleasant.

p.s. Look sharp for Rita Moreno making the most of her one scene in this movie.

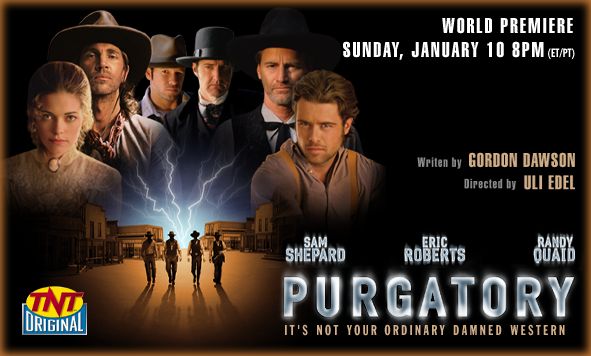

One of the happy outcomes of the cable television revolution was that more stations were competing to brand themselves with audiences, and one method some of them chose was to start making their own films. The budgets were not as large as what Hollywood might provide, but the results were often more original. Such is the case with Uli Edel’s unconventional western

One of the happy outcomes of the cable television revolution was that more stations were competing to brand themselves with audiences, and one method some of them chose was to start making their own films. The budgets were not as large as what Hollywood might provide, but the results were often more original. Such is the case with Uli Edel’s unconventional western

“

“