Supplementing my recommendation of The Charmer, I offer another Patrick Hamilton adaptation, albeit one that departs more substantially from the original novel: 1945’s Hangover Square.

The plot: In Edwardian London, brilliant, troubled classical composer George Bone (Laird Cregar) suffers fugue states during which he commits violent acts which he cannot recall afterwards. As Bone attempts to hold his psyche together long enough to complete a concerto, a scheming, alluring dance hall tart named Netta Longdon (Linda Darnell) tempts him in every way to devote his talents instead towards producing popular songs that will catapult her to fame. When George finally realizes that Netta is manipulating him, his mind snaps once more, propelling forward this dark tale of suspense, crime, and emotional anguish.

I am going to start my analysis of this film by getting the unpleasant bit out straightaway. The middling script of Hangover Square was written by Alfred Edgar, under the pen name Barré Lyndon (Presumably he was a Thackeray fan). Edgar drained the trenchant political and psychological observations from Hamilton’s novel (which was set during Hitler’s rise to power), added some clunky expositional exchanges while leaving other important elements of the plot strangely unexplained, and concocted a character who makes little sense (Dr. Allan Middleton, played by George Sanders, who is a clinical psychiatrist but is also somehow a front-line police detective and also apparently a romantic rival of George Bone though this is dropped after a single needless scene). Edgar’s is by no means a terrible screenplay, but given the source material — Hangover Square is generally considered Hamilton’s best novel — it should have been better.

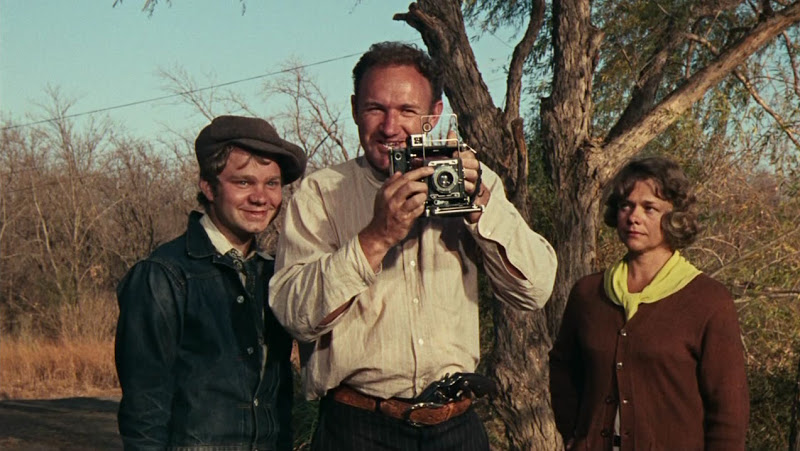

Fortunately, other elements of Hangover Square are so remarkable that they overcome the script’s flaws. The film is anchored by scintillating performances by two sadly short-lived talents: Cregar and Darnell. The character of George Bone might easily have repelled the audience, but Cregar conveys such vulnerability and ingenuousness that the audience sympathizes with him anyway. A talented musician in his own right, Cregar is also completely believable in his composing and performance scenes. Darnell, only 22 years old at he time, is just as good at being bad. She keeps every man in the movie dancing on a string with her lovely face, artful conversational dodges, and sexual ruthlessness. One central aspect of the book that the film does maintain are the scenes of love struck George letting Netta hurt him, disregard him, and demean him; Cregar and Darnell play these just right.

The visuals of the movie are as rewarding as the performances. The sets are handsome, the costumes expertly done, and the editing is spot on. On top of all that, the brilliant Joseph LaShelle (whose film noir work I have praised before) contributes gorgeously shadowy cinematography and a particularly superb tracking shot at the climax.

The other undeniable pleasure of Hangover Square is Bernard Herrmann’s score, one of the best in his storied career. Herrmann had to write not just the usual movie theme music, but also the piece that Bone is striving to compose and plays in the arresting final scene. The result — Concerto Macabre — is a knockout.

Hangover Square re-united much of the team that made another of my recommendations, The Lodger, the year before, but the second production was not a happy set. Stevens hated his closing line and got into a row about it with producer Robert Bassler that allegedly ended in fisticuffs. Cregar loved the novel and was angry about how it had been drastically changed in the script, and he and director John Brahm clashed throughout the production. Cregar was also struggling with health problems stemming from his attempts to dramatically reduce his weight, including through amphetamine use. He died two months before Hangover Square was released, but at least fate made his last scene on screen an unforgettable image that will stay with viewers of this film for many a moon.