As an ex-academic, BBC comedy writer, and member of The Savile Club, Stephen Potter had ample opportunity to observe all the ways British culture provided to “win without cheating”: the perfectly timed cough when your golf opponent is about to tee off, the lightly dismissive remark that flusters a fellow diner in the midst of his lengthy anecdote, the artful humblebrag that reduces listeners to simpering admiration. It’s all part of what we now call “gamesmanship”, a neologism Potter popularized in 1947 in the first of several best-selling parodies of self-help books. In 1960, Hal Chester, Patricia Moyes, Frank Tarloff, and Peter Ustinov (the latter two uncredited) fashioned Potter’s works into the script for a quintessentially British comedy: School for Scoundrels.

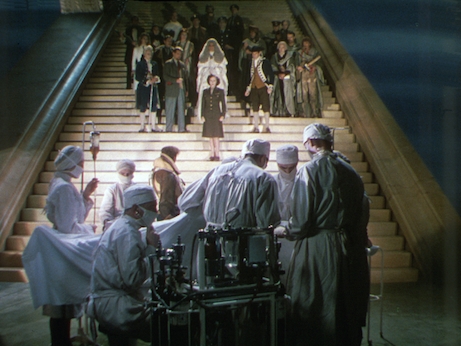

The plot: Henry Palfrey (Ian Carmichael, made for these sorts of roles) is the ineffectual inheritor of his father’s company. Though Henry is ostensibly the boss, his employees do not respect him, and neither for that matter does anyone else. His life as a polite doormat takes a sudden turn when something very good literally falls into his path: the utterly charming April Smith (a winsome Janette Scott). But he soon has a romantic rival in the form of ultra-smooth cad Raymond Delauney (Terry-Thomas, made for those sorts of roles), who dazzles April and consistently gets the better of Henry. In desperation, Henry enrolls in a “School of Lifemanship” overseen by Headmaster S. Potter (ahem). This cynical, crafty instructor (Alastair Sim, always a joy) teaches Henry gamesmanship, oneupmanship, and woomanship. Thus fortified, he returns to seek revenge on Raymond and win April’s heart.

The director’s credit for this little comic gem reads Robert Hamer, who made two of my other recommendations, the hilarious dark comedy Kind Hearts and Coronets and the trend-setting noirish kitchen sink drama It Always Rains on Sunday. Unfortunately, by 1960 his alcoholism was out of control and he was fired in the middle of this film. He never directed again and died a few years later. Hal Chester and Cyril Frankel are said to have to directed the remaining scenes.

Having three directors would ruin most movies. But the professionalism and experience of the cast shines through despite at all, with all the leads doing well, especially Terry-Thomas in perhaps the best performance of his career. The talented supporting players include many staples of British comedy such as John Le Mesurier, Hattie Jacques, Irene Handl, Dennis Price, and Peter Jones.

The other enormous virtue is the mordant script which sets up numerous funny scenes in which characters find ingenious ways to get the edge on each other. The humor is sometimes farcical and at other times subtle, a mix that may not be to all tastes but that I found most pleasing. If not at the level of the most lauded British post-war comedies, School for Scoundrels still delivers many laughs as well as a surprisingly sweet romantic resolution.

p.s. Janette Scott is the daughter of British television legend Dame Thora Hird.