Of all the talented people I mention on this website, I don’t think any name appears more often than Richard Matheson. Working almost entirely within the science-fiction/horror genre, this prolific writer managed to tell stories that entertained a broad audience while also being consistently intelligent and in some cases also conveying considerable psychic weight. No adaptation of his work illustrates better than the classic 1957 movie The Incredible Shrinking Man.

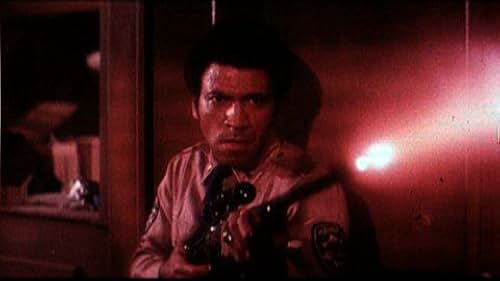

The plot: The Careys, an attractive, happy, married couple are out boating when a mysterious fog on the water scatters a strange, shimmering material on Scott (Grant Williams). Six months later, after being exposed to some pesticide, his body begins to shrink, inch by inch. Doctors conclude that some sort of chemical or radiological malady has afflicted Scott; they can slow it down but not stop it. Helplessly and bitterly, Scott becomes smaller physically as well as in other respects: he can no longer hold a job, becomes resentful and controlling of his wife Louise (Randy Stuart), and is widely mocked. His resentment turns to terror when he is left alone in the house with the family cat and subsequently trapped in a dank basement with one of the scariest spiders in screen history.

There’s much to admire in this film both technically and thematically. The production design and special effects are trend-setting, and six decades later still impress and unnerve modern audiences. Williams and Stuart, whose subsequent careers surprisingly did not flower, deliver strong performances as ordinary people coping with extraordinary stress on themselves and their marriage. And director Jack Arnold turns in the best effort of his career.

But what really makes the movie is Matheson’s story, which he published as a novel and then co-adapted with Richard Allen Simmons for the screenplay (although Matheson did not value Simmons’ changes and refused to share an on screen credit with him). The story’s strengths include a highly original premise, believable dialogue, crisp plotting, and engaging philosophic themes.

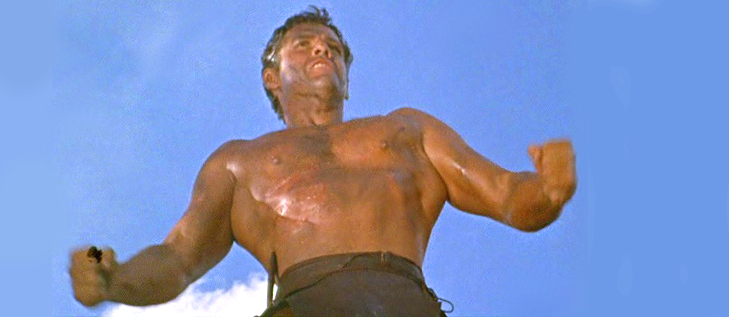

Many people read this film as being about threatened post-war masculinity, seen for example in Scott’s anxiety over becoming smaller than Louise, his inability to provide financially for her, and him eventually being forced to live in a dollhouse she sets up for him. Although it’s never made explicit, the couple’s sexual relationship also ends, and there’s something pathetic yet touching in the protagonist going from being a virile, confident, 6 footer in the opening scene to showing sudden, desperate interest in a pretty, pint-sized circus performer (April Kent)….until he shrinks below her size too. Yet the film works just as well as a more general reflection on the human search for meaning in the face of our trivial place in the universe and the inevitability of death. There is no dialogue during the closing third of the movie, only Scott narrating his existential predicament, which ultimately is surprisingly profound, even moving.

I have also a recommended Jack Arnold’s comparatively lightweight but quite entertaining B-movie Tarantula, about a giant spider who terrorizes a town (There’s a movie legend that Arnold used the same tarantula in this film, which seems implausible). It’s thought-provoking to reflect on why a giant tarantula chasing normal sized people in that movie is less scary than a normal sized tarantula chasing a miniaturized man here. Partly it’s the camerawork, which makes the audience see the spider and everything else in the basement from Scott Carey’s vulnerable perspective. The other part is the extreme isolation of the character. In Tarantula, there are many people who are towered over by the spider, whereas here Carey is utterly alone not only in the battle but in the universe, a recurring theme in the work of the legendary Richard Matheson.